A couple of years ago Jan and I were going through some of my father's papers and found a very old typed copy of the ballad "Grimbles and the Gnad" which was written by C J Dennis and first published on Page 18 of The Weekly Times Annual on 4 November 1915. Dad had obviously taken a real liking to the story - and after reading it I can understand why.

The main intent of the story, as I see it, is to highlight in a humorous way the dangers of introducing exotic (or non-native) organisms to an environment in an attempt to control some other organism that is considered a pest for whatever reason.

The web address of an internet site that holds a copy of "Grimbles and the Gnad" is http://www.middlemiss.org/lit/authors/denniscj/backblocklater/grimbles.html

Estimated reading time is 5 minutes as it takes a little while to get the hang of the lingo. Enjoy!

The Ochre Archives blogsite enables me to record for my own future reference and to share various learnings and experiences, many of which are connected with the farm that Jan and I purchased in 2003, "Ochre Arch", Grenfell, Australia. Readers should carry out their own independent checks before acting on any of the comments contained in this blogsite. To have your say on whatever I've said, click on the 'comments' link that appears below the blog article and follow the prompts.

Tuesday, 23 May 2006

Sunday, 21 May 2006

Aboriginal approach to bushfire control

In response to my last blog (which mentions the Wiradjuri people and fire), Col Freeman sent me though a link to a lengthy but fascinating article written by George Main and published on the La Trobe Library website during October 2004 that in one section describes the technique used by the Wiradjuri people to control bushfires. Thanks for sending the link through, Col.

Those who would like to read the article can access it at http://www.lib.latrobe.edu.au/AHR/archive/Issue-August-2004/main.html

Those who would like to read the article can access it at http://www.lib.latrobe.edu.au/AHR/archive/Issue-August-2004/main.html

Ochre Arch History Part 4 - Pre European Settlement

Pre arrival of the Aborigines

There is general consensus that the Aborigines arrived on the Australian continent somewhere between 40-60,000 years ago and that during this period there has been a major decline in the species of very large mammals, or megafauna. There is great debate as to the cause of the extinction of these megafauna species, ranging from the impact of early people of Australia hunting them to extinction and / or using fire to alter the environment, to significant climatic changes over the period (especially a very intense dry spell around 26,000 years ago), through to the effect of new animals coming into Australia as we drew ever closer to south-east Asia (including disease or infestation bought along with the invading species).

Allan Savory in his book “Holistic Management – A New Framework for Decision Making” (ISBN 1-55963-488-X) makes the following comments on Page 6. “By the time humans acquired the use of fire, and our technology had grown sophisticated enough to enable us to reach and settle new continents or isolated islands, we were capable of inflicting enormous damage. Within 400 years of their arrival in New Zealand, the Maori had exterminated nearly all the flightless birds, including 12 different species of the giant (550 pound) moa, and decimated much of the seashore life. Following the arrival of the Aborigines in Australia … over 80 percent of the large mammalian genera became extinct. The fires deliberately set by the Aborigines when hunting, or to limit the extent of uninhabitable rainforest, led to a dramatic increase in soil erosion, the abrupt disappearance of fire sensitive plant species, and a dramatic Increase in fire-dependent species, such as eucalypts. In North America, over 70 percent of the large mammalian genera became extinct following the arrival of Native Americans around 12,000 years ago.”

I have included the above purely to make the point that the environment on and around Ochre Arch has changed (possibly) quite dramatically throughout the millennia. I am not attempting to attribute blame for this change. Let's not forget that since the arrival of European settlers there has been a decline of over 25 % in the number of ALL mammal species in Australia.

For those interested in learning more about the species of Australian megafauna that are now extinct I strongly recommend you spend a few minutes checking out the web address http://abc.net.au/science/ausbeasts/factfiles. Imagine having 2 tonne wombats and marsupial lions roaming around!

Local Aborigines

Ochre Arch is in the South West Slopes region of NSW, and from an indigenous Australia perspective falls within ‘Wiradjuri country’. Wiradjuri refers to the Aboriginal language that was, and is still, spoken by the various family or kinship groups throughout the region and is said to mean ‘people of the three rivers’; with those rivers being the Macquarie, Lachlan and Murrumbidgee. I know little of the history of the Wiradjuri people but understand the land area they occupied and their impact declined significantly between 1830 and 1850 in connection with the territorial spread of the early settlers. This period ties in with the establishment of the Pinnacle Run mentioned in a prior blog. The Aboriginal communities nearest to Ochre Arch that I am aware of are at Forbes and Cowra.

We have found a couple of artefacts on Ochre Arch, and as I’ve mentioned in another blog we renamed the property from to Ochre Arch following a visit from Aboriginal archaeologist Sue Hudson in September 2005. Sue discovered that the natural ironstone arch in one of our creeks had been mined by Aborigines for ochre.

I contacted Sue Hudson to find out a little more about the Wiradjuri language. She informed me that:

1. 'Wiradjuri' is still spoken and it is offered a language course out of the Australian National University in Canberra.

2. 'Wiradjuri' refers to a language group. This means that all of the people in the area spoke it but it differed from place to place in that you can understand what they are saying but it sounds different. Similar to what occurs in the counties of England; for example Yorkshire compared to London.

3. Language groups are distinct but in areas where there are adjacent language groups bits of each language can be understood by neighbours, For example, the English spoken by the English from England compared to Welch from the Welch in Wales. Some neighbouring Aboriginal language groups are Wiradjuri, Wongarbon and Gamaroi.

4. Aboriginal groups are not referred to as tribes - there are no tribes as such. There are family or kinship groups within each area. For example, those living around Grenfell would be related to one another, some close, some distant. Their marriage partners came from groups such as, say, Peak Hill, Cowra or Condobolin that would meet at social/ceremonial occasions. Their system of who could/couldn't marry is very strict and is called 'moieties'.

5. An excellent publication to learn more about Aborigines is "The World of the First Australians" by RM & CH Berndt.

When Jan and I were visiting Wallace Rockhole in the Northern Territory recently the local tour guide, Ken, made a comment about land connection and Aborigines that is worth mentioning. Most of us who live in Australia speak of ‘owning the land’ whilst the Aborigines believe they ‘belong to’ the land. A very different perspective indeed.

Link to Ochre Arch History Part 1

Link to Ochre Arch History Part 2

Link to Ochre Arch History Part 3

Link to Ochre Arch History Part 5

There is general consensus that the Aborigines arrived on the Australian continent somewhere between 40-60,000 years ago and that during this period there has been a major decline in the species of very large mammals, or megafauna. There is great debate as to the cause of the extinction of these megafauna species, ranging from the impact of early people of Australia hunting them to extinction and / or using fire to alter the environment, to significant climatic changes over the period (especially a very intense dry spell around 26,000 years ago), through to the effect of new animals coming into Australia as we drew ever closer to south-east Asia (including disease or infestation bought along with the invading species).

Allan Savory in his book “Holistic Management – A New Framework for Decision Making” (ISBN 1-55963-488-X) makes the following comments on Page 6. “By the time humans acquired the use of fire, and our technology had grown sophisticated enough to enable us to reach and settle new continents or isolated islands, we were capable of inflicting enormous damage. Within 400 years of their arrival in New Zealand, the Maori had exterminated nearly all the flightless birds, including 12 different species of the giant (550 pound) moa, and decimated much of the seashore life. Following the arrival of the Aborigines in Australia … over 80 percent of the large mammalian genera became extinct. The fires deliberately set by the Aborigines when hunting, or to limit the extent of uninhabitable rainforest, led to a dramatic increase in soil erosion, the abrupt disappearance of fire sensitive plant species, and a dramatic Increase in fire-dependent species, such as eucalypts. In North America, over 70 percent of the large mammalian genera became extinct following the arrival of Native Americans around 12,000 years ago.”

I have included the above purely to make the point that the environment on and around Ochre Arch has changed (possibly) quite dramatically throughout the millennia. I am not attempting to attribute blame for this change. Let's not forget that since the arrival of European settlers there has been a decline of over 25 % in the number of ALL mammal species in Australia.

For those interested in learning more about the species of Australian megafauna that are now extinct I strongly recommend you spend a few minutes checking out the web address http://abc.net.au/science/ausbeasts/factfiles. Imagine having 2 tonne wombats and marsupial lions roaming around!

Local Aborigines

Ochre Arch is in the South West Slopes region of NSW, and from an indigenous Australia perspective falls within ‘Wiradjuri country’. Wiradjuri refers to the Aboriginal language that was, and is still, spoken by the various family or kinship groups throughout the region and is said to mean ‘people of the three rivers’; with those rivers being the Macquarie, Lachlan and Murrumbidgee. I know little of the history of the Wiradjuri people but understand the land area they occupied and their impact declined significantly between 1830 and 1850 in connection with the territorial spread of the early settlers. This period ties in with the establishment of the Pinnacle Run mentioned in a prior blog. The Aboriginal communities nearest to Ochre Arch that I am aware of are at Forbes and Cowra.

We have found a couple of artefacts on Ochre Arch, and as I’ve mentioned in another blog we renamed the property from to Ochre Arch following a visit from Aboriginal archaeologist Sue Hudson in September 2005. Sue discovered that the natural ironstone arch in one of our creeks had been mined by Aborigines for ochre.

I contacted Sue Hudson to find out a little more about the Wiradjuri language. She informed me that:

1. 'Wiradjuri' is still spoken and it is offered a language course out of the Australian National University in Canberra.

2. 'Wiradjuri' refers to a language group. This means that all of the people in the area spoke it but it differed from place to place in that you can understand what they are saying but it sounds different. Similar to what occurs in the counties of England; for example Yorkshire compared to London.

3. Language groups are distinct but in areas where there are adjacent language groups bits of each language can be understood by neighbours, For example, the English spoken by the English from England compared to Welch from the Welch in Wales. Some neighbouring Aboriginal language groups are Wiradjuri, Wongarbon and Gamaroi.

4. Aboriginal groups are not referred to as tribes - there are no tribes as such. There are family or kinship groups within each area. For example, those living around Grenfell would be related to one another, some close, some distant. Their marriage partners came from groups such as, say, Peak Hill, Cowra or Condobolin that would meet at social/ceremonial occasions. Their system of who could/couldn't marry is very strict and is called 'moieties'.

5. An excellent publication to learn more about Aborigines is "The World of the First Australians" by RM & CH Berndt.

When Jan and I were visiting Wallace Rockhole in the Northern Territory recently the local tour guide, Ken, made a comment about land connection and Aborigines that is worth mentioning. Most of us who live in Australia speak of ‘owning the land’ whilst the Aborigines believe they ‘belong to’ the land. A very different perspective indeed.

Link to Ochre Arch History Part 1

Link to Ochre Arch History Part 2

Link to Ochre Arch History Part 3

Link to Ochre Arch History Part 5

Saturday, 20 May 2006

R M Williams' Autobiography

Whilst waiting at Alice Springs for our flight back to Melbourne on 13 May 2006 following our 5 day Sahara Adventures red centre tour I bought a copy of R M (Reginald Murray) Williams autobiography (ISBN 0-7251-0753-7), and finished reading it last night. What an amazing read about an amazing bloke! Essential reading in my view for anyone seriously interested in the study of the development of primary industry in Australia. I’ve recorded below a just few of the things that I learned and want to remember or views he expressed that I think are worth sharing. What’s below is just the ‘tip of the iceberg’ of what his book has to offer.

How Aborigines in desert areas made fire

RM spent a great many years in direct contact with Aboriginal people, meeting some who he believes had no prior contact with ‘the white man’. He held them in high regard, recognizing their amazing skills, and deep understanding of the environment in which they lived. On page 28 he explains how they made fire:

“To make fire they shredded dray kangaroo dung into a crack in a fairly substantial piece of wood, then two of them would rub the hard burnished surface of a spear-thrower across the crack, causing smouldering material from the log to fall into the tinder in the crack. When enough had gathered they tipped it out into a bunch of dried grass, waiving this into the air to fan it into a flame. Thus they seemed to make fire without much effort; it wasn’t quite as easy as striking a match but it took only a few minutes.”

Aborigines and religion

The core content of RM’s autobiography is obviously his recounting the major events of his life, but he puts forward his thoughts on Australia and the world at large, including the subject of religion. On page 29 he shares what he comments on the religious beliefs of the Aboriginal desert people he met during the 1920’s and beyond.

“These desert people lived in a state of mental contentment. I attribute this to the centuries-old practice of a religion that was not a spiritual seeking but rather a total immersion in the mysticism that provided a pragmatic solution to any problem of survival. Whereas my needs for spiritual satisfaction included a promise of change, a hope for something better, the Aborigines – and in fact most Stone Age people – live and die content in the complete religion that explains an environment they do not want to see altered.”

Aboriginal mission without white man interference

In about 1934 RM received a call from Dr Charles Duguid who he describes on Page 64 as ‘a surgeon with considerable care for the Aborigines.” One outcome of this contact was the formation of a Committee (with RM as a member) which established a medical mission for the Aborigines at Ernabella in the Musgraves, and Dr Duguid was “determined it should be one in which the natives were left to follow their own way of life … where they would have time to adjust to the changes that were coming whether they liked them or not, and thus have a chance of survival. The most basic feature was the concept of freedom – no interference with tribal customs, no compulsion and no imposition of white man way of life”. On Page 66 RM goes on to say “Ernabella Mission was to become a big factor in preserving the state of Aborigines in the Musgraves, and it still stands as something of a bastion against white intrusion.”

Discipline and Aboriginal children

On Page 66 RM talks about how the Aboriginal people did not disciplined their children. In his words “there was no need, for the struggle of life itself was a discipline. Long marches on a hungry belly, fierce laws that demanded death if broken, skill to kill as the essential element for survival, and a surrounding of enemies produced by a society of people made honest by necessity.”

The Bushman’s Handbook

On Page 68 RM talks about how he wrote and published The Busman’s Handbook, which was designed to “assist young bushmen and others who wanted to make things of real worth and serviceability: saddles, boots, stockwhips, belts – anything that could be made of leather, beginning with the tanning of the hide.”

RM on the behaviour of modern day politicians

On Page 73 RM talks about his involvement in the formation of the Australian Rough Riders Association and goes on to say how “In this organization I made many life long friends, fellows who have proved themselves to be champions in every way, and when I hear our politicians abusing each other in Parliament I recall that none of our members would speak in such a manner unless he were prepared to do battle on the grass.”

Man’s responsibility for the environment

On Page 127 RM explains: “The essential difference between man and animals is that man has a … quality of being able to change his environment. When he plants a seed he does so with the knowledge that some day it will become a tree, and that the tree will provide shade or sustenance. He plants a garden with the knowledge that some day it will give him pleasure. He preconceives the outcome of his activities. To carry this argument to its logical conclusion we must arrive at the decision that we are responsible for the environment in which we live.”

Cattle and salt licks

On Pages 140 and 141 RM explains how he used to use salt licks as a mechanism to integrate his own cattle with those they were wild, and in this way he was able to muster most that were on the country he had legal access to. It was toward the end of the drought years of the late 1960’s that the Queensland Department of Primary Industry “had discovered that cattle given licks of a mixture of molasses and urea and phosphoric acid maintained health and condition even though the available grazing was extremely poor, and they would ingest materials they would normally ignore, such as wattle and whitewood leaves, and prickly pear.”

Adaptation of the Pioneers to the environment

On Page 183 RM sets out many of the ways in which the Australian Pioneers (especially the cattlemen) developed methods and attire for survival. I’ve personally worn elastic sides boots from the time I was very young, and until reading RM's Autobiography confess that I was not aware of the real reason they were invented. As RM explains, the cattleman’s “boots were made easy to get on, because of the need for fast action if cattle rushed in the night.”

How Aborigines in desert areas made fire

RM spent a great many years in direct contact with Aboriginal people, meeting some who he believes had no prior contact with ‘the white man’. He held them in high regard, recognizing their amazing skills, and deep understanding of the environment in which they lived. On page 28 he explains how they made fire:

“To make fire they shredded dray kangaroo dung into a crack in a fairly substantial piece of wood, then two of them would rub the hard burnished surface of a spear-thrower across the crack, causing smouldering material from the log to fall into the tinder in the crack. When enough had gathered they tipped it out into a bunch of dried grass, waiving this into the air to fan it into a flame. Thus they seemed to make fire without much effort; it wasn’t quite as easy as striking a match but it took only a few minutes.”

Aborigines and religion

The core content of RM’s autobiography is obviously his recounting the major events of his life, but he puts forward his thoughts on Australia and the world at large, including the subject of religion. On page 29 he shares what he comments on the religious beliefs of the Aboriginal desert people he met during the 1920’s and beyond.

“These desert people lived in a state of mental contentment. I attribute this to the centuries-old practice of a religion that was not a spiritual seeking but rather a total immersion in the mysticism that provided a pragmatic solution to any problem of survival. Whereas my needs for spiritual satisfaction included a promise of change, a hope for something better, the Aborigines – and in fact most Stone Age people – live and die content in the complete religion that explains an environment they do not want to see altered.”

Aboriginal mission without white man interference

In about 1934 RM received a call from Dr Charles Duguid who he describes on Page 64 as ‘a surgeon with considerable care for the Aborigines.” One outcome of this contact was the formation of a Committee (with RM as a member) which established a medical mission for the Aborigines at Ernabella in the Musgraves, and Dr Duguid was “determined it should be one in which the natives were left to follow their own way of life … where they would have time to adjust to the changes that were coming whether they liked them or not, and thus have a chance of survival. The most basic feature was the concept of freedom – no interference with tribal customs, no compulsion and no imposition of white man way of life”. On Page 66 RM goes on to say “Ernabella Mission was to become a big factor in preserving the state of Aborigines in the Musgraves, and it still stands as something of a bastion against white intrusion.”

Discipline and Aboriginal children

On Page 66 RM talks about how the Aboriginal people did not disciplined their children. In his words “there was no need, for the struggle of life itself was a discipline. Long marches on a hungry belly, fierce laws that demanded death if broken, skill to kill as the essential element for survival, and a surrounding of enemies produced by a society of people made honest by necessity.”

The Bushman’s Handbook

On Page 68 RM talks about how he wrote and published The Busman’s Handbook, which was designed to “assist young bushmen and others who wanted to make things of real worth and serviceability: saddles, boots, stockwhips, belts – anything that could be made of leather, beginning with the tanning of the hide.”

RM on the behaviour of modern day politicians

On Page 73 RM talks about his involvement in the formation of the Australian Rough Riders Association and goes on to say how “In this organization I made many life long friends, fellows who have proved themselves to be champions in every way, and when I hear our politicians abusing each other in Parliament I recall that none of our members would speak in such a manner unless he were prepared to do battle on the grass.”

Man’s responsibility for the environment

On Page 127 RM explains: “The essential difference between man and animals is that man has a … quality of being able to change his environment. When he plants a seed he does so with the knowledge that some day it will become a tree, and that the tree will provide shade or sustenance. He plants a garden with the knowledge that some day it will give him pleasure. He preconceives the outcome of his activities. To carry this argument to its logical conclusion we must arrive at the decision that we are responsible for the environment in which we live.”

Cattle and salt licks

On Pages 140 and 141 RM explains how he used to use salt licks as a mechanism to integrate his own cattle with those they were wild, and in this way he was able to muster most that were on the country he had legal access to. It was toward the end of the drought years of the late 1960’s that the Queensland Department of Primary Industry “had discovered that cattle given licks of a mixture of molasses and urea and phosphoric acid maintained health and condition even though the available grazing was extremely poor, and they would ingest materials they would normally ignore, such as wattle and whitewood leaves, and prickly pear.”

Adaptation of the Pioneers to the environment

On Page 183 RM sets out many of the ways in which the Australian Pioneers (especially the cattlemen) developed methods and attire for survival. I’ve personally worn elastic sides boots from the time I was very young, and until reading RM's Autobiography confess that I was not aware of the real reason they were invented. As RM explains, the cattleman’s “boots were made easy to get on, because of the need for fast action if cattle rushed in the night.”

Monday, 15 May 2006

Our Red Centre Tour - May 2006 - Itinerary

Jan and recently traveled to the ‘Red Centre’ of Australia for a 5 day camping tour with Sahara Adventures. What follows is the base itinerary. Obviously we have many more memories and photographs of our trip which we’ll share with friends over time.

8th May 2006 Melbourne to Ayers Rock

We caught the 08.45 flight from Melbourne to Ayers Rock Airport and then the courtesy bus to the Outback Pioneer Hotel at Ayers Rock Resort. At 13.45 we were picked up by Sahara Adventures. There were 19 people in all on the bus; including the Tour Guide, 14 people for the 5 day Tour and 4 doing the 3 day Tour. Lunch was at the Ayers Rock Sahara Adventures permanent campsite. Our group then went to Kata Tjuta (The Olgas) where we did the Walpa Gorge walk. From there we drove to the public viewing area at Uluru to watch the sun set before returning to the campsite for dinner and sleep.

9 May 2006 Uluru to Kings Creek Station

We reached Uluru before the 07.12 sunrise, with our Tour Guide having driven us around the entire base beforehand. Phillip and 5 others climbed Uluru, whilst Jan and the rest of the group walked the 9.5 km around the base of the Rock. After all gathering at the vehicle in the car park for morning tea, we did the Mala walk with our Tour Guide.

It was then back to the campsite to have lunch, pack up and hit the road; stopping first at Ayers Rock Resort, Yulara to check out the shops while the vehicle was refueled.

We traveled to Kings Creek Station via Lasseter Highway and then Luritja Road, stopping on the way at Curtin Springs Roadhouse (has a small native bird aviary) for fuel, then Mount Connor Lookout (Mount Connor is a large flat topped hill 3 times as big around as Uluru at 27 km); and off to the side of Luritja road at one point to collect firewood, arriving at the Sahara Adventures King Creek Station permanent campsite for the night. Just prior to dark Jan and I did the 35 minute helicopter flight over Kings Canyon and Petermann Pound. Our Tour Guide cooked dinner using camp ovens.

10 May 2006 Kings Creek Station to Glen Helen

At 06.45 we were all packed up and on the road to Kings Canyon. Most of the group (us included) did the 4 hour walk around the canyon, stopping briefly en-route for morning tea at the Garden of Eden. The rest of the group walked up and back along the base of the canyon. After refueling at Kings Canyon Resort we headed along the Mereenie Loop for about 10 minutes and pulled off to a designated stop at the top of a ridge for a picnic lunch.

After lunch we continued along the Mereenie Loop. We saw evidence of the Mereenie Oil and Gas field off to the right at one point, proceeded through Gardiner Range where we had an unplanned stop allowing some of us to photograph some wild horses, and another to ascertain the source of a new vehicle noise just forward of the left hand rear wheel, passed the Aboriginal Mission near Katapata Gap, and turned left along Route 2 toward Glen Helen. We saw Goss Bluff meteor crater from a distance off to the right and stopped for a break at Tylers Pass lookout where a group photograph was taken. On arriving at Glen Helen (16.45) we stopped at the Hotel while waiting for the other Sahara Adventures 4WD vehicle to arrive and take those who had completed the “Sahara Adventures 3 day trip” with us back to Alice Springs. It was then on to the Sahara Adventures permanent campsite to unpack, have dinner and sleep. During the wait for the meal to cook the ‘blokes’ went to the pub for an hour or so.

11 May 2006 Glen Helen to Wallace Rockhole

After breakfast Jan and I and another couple walked across the river to the mouth of the Glen Helen Gorge to see the water hole and take some photographs. The group was ‘on the road’ by about 08.30 with the first stop being the Mount Solomon lookout near Glen Helen. From there we went to Ormiston Gorge, with about half the group (us included) doing the 2 hour walk with our Tour Guide and the others walking up and back along the bottom of the Gorge. Our Tour Guide cooked hamburgers for lunch on one of the gas barbecues at the camping area.

After lunch we proceeded east along (Albert) Namatjira Drive to Ellery Creek / Big Hole where we spent some time relaxing in the sun near the edge of the water hole. I headed off on my own and climbed part way up the ridge behind the waterhole to explore the cave that can be seen from the edge of the water hole.

It was then on to Wallace Rockhole. On the way in to this ‘dry’ Aboriginal community we were pulled up by the Police who checked to make sure we were not bringing alcohol in to the area. We stopped at the General Store which is run by ‘Ken’ who also happens to be the key tourist person for the community. After leaving our gear in the tents at the Sahara Adventures permanent campsite Ken took us all on a drive/walk up to the Wallace Rockhole while our Tour Guide stayed behind and started preparations for dinner. Ken shared some excellent information with us about the Aboriginal people and concluded the tour by giving us access to the Arts Centre where many of us purchased locally manufactured items. After dinner we all talked for quite some time around the camp fire.

12 May 2006 Wallace Rockhole to Alice Springs

We were on the road by about 06.45. First stop was at the (Albert) Namatjira Monument on Larapinta Drive, then on to Hermannsburg where we dropped off the trailer lightening the load for our first bit of real 4 wheel-driving out to the Finke Gorge National Park where we saw the Kalarranga Lookout and then moved on to Palm Valley to see the ancient palms and rock formations that abound in the Gorge.

After a walk that takes about 1.5 hours we enjoyed a picnic lunch at one of the eating and toilet block areas in the National Park before returning to Hermannsburg to pick up the trailer / check out the local store and head east along Larapinta Drive toward Alice Springs. We spent a couple of hours at Standley Chasm, and proceeded on to Alice Springs were our Tour Guide took us past a couple of tourist spots and dropped each of us at our accommodation locations. Jan and I stayed at the All Seasons Diplomat Motel. After walking around Todd Mall, we enjoyed a drink at the Todd Tavern and some shopping before dining at the Overlanders Steakhouse.

13 May 2006 Alice Springs to Melbourne

After breakfast we did the “Alice Wanderer ‘Hop on – Hop off’ Alice Explorer Town Tour”, catching the bus out the front of our Motel at 08.50. The tour duration was 1 hour 10 minutes and the trip took us past the Todd Mall, Old Telegraph Station, School of the Air, Anzac Hill (the tour includes an allowance of a couple of minutes to walk around and take some photographs), Panorama Guth Art Gallery, Royal Flying Doctor Base, Alice Springs Reptile Centre, Alice Springs Cultural Precinct (including the Museum of Central Australia, Aviation Museum, Araluen Art and Sculpture Centre, Historic Cemetery [with the grave for Albert Namatjira]), Road Transport Hall of Fame, Old Ghan Train, Date Gardens and the Olive Pink Native Species Gardens.

When we finished the tour we packed up our bags at the Motel and took a cab to the Airport for our 11.30 flight back to Melbourne, arriving 14.25.

8th May 2006 Melbourne to Ayers Rock

We caught the 08.45 flight from Melbourne to Ayers Rock Airport and then the courtesy bus to the Outback Pioneer Hotel at Ayers Rock Resort. At 13.45 we were picked up by Sahara Adventures. There were 19 people in all on the bus; including the Tour Guide, 14 people for the 5 day Tour and 4 doing the 3 day Tour. Lunch was at the Ayers Rock Sahara Adventures permanent campsite. Our group then went to Kata Tjuta (The Olgas) where we did the Walpa Gorge walk. From there we drove to the public viewing area at Uluru to watch the sun set before returning to the campsite for dinner and sleep.

9 May 2006 Uluru to Kings Creek Station

We reached Uluru before the 07.12 sunrise, with our Tour Guide having driven us around the entire base beforehand. Phillip and 5 others climbed Uluru, whilst Jan and the rest of the group walked the 9.5 km around the base of the Rock. After all gathering at the vehicle in the car park for morning tea, we did the Mala walk with our Tour Guide.

It was then back to the campsite to have lunch, pack up and hit the road; stopping first at Ayers Rock Resort, Yulara to check out the shops while the vehicle was refueled.

We traveled to Kings Creek Station via Lasseter Highway and then Luritja Road, stopping on the way at Curtin Springs Roadhouse (has a small native bird aviary) for fuel, then Mount Connor Lookout (Mount Connor is a large flat topped hill 3 times as big around as Uluru at 27 km); and off to the side of Luritja road at one point to collect firewood, arriving at the Sahara Adventures King Creek Station permanent campsite for the night. Just prior to dark Jan and I did the 35 minute helicopter flight over Kings Canyon and Petermann Pound. Our Tour Guide cooked dinner using camp ovens.

10 May 2006 Kings Creek Station to Glen Helen

At 06.45 we were all packed up and on the road to Kings Canyon. Most of the group (us included) did the 4 hour walk around the canyon, stopping briefly en-route for morning tea at the Garden of Eden. The rest of the group walked up and back along the base of the canyon. After refueling at Kings Canyon Resort we headed along the Mereenie Loop for about 10 minutes and pulled off to a designated stop at the top of a ridge for a picnic lunch.

After lunch we continued along the Mereenie Loop. We saw evidence of the Mereenie Oil and Gas field off to the right at one point, proceeded through Gardiner Range where we had an unplanned stop allowing some of us to photograph some wild horses, and another to ascertain the source of a new vehicle noise just forward of the left hand rear wheel, passed the Aboriginal Mission near Katapata Gap, and turned left along Route 2 toward Glen Helen. We saw Goss Bluff meteor crater from a distance off to the right and stopped for a break at Tylers Pass lookout where a group photograph was taken. On arriving at Glen Helen (16.45) we stopped at the Hotel while waiting for the other Sahara Adventures 4WD vehicle to arrive and take those who had completed the “Sahara Adventures 3 day trip” with us back to Alice Springs. It was then on to the Sahara Adventures permanent campsite to unpack, have dinner and sleep. During the wait for the meal to cook the ‘blokes’ went to the pub for an hour or so.

11 May 2006 Glen Helen to Wallace Rockhole

After breakfast Jan and I and another couple walked across the river to the mouth of the Glen Helen Gorge to see the water hole and take some photographs. The group was ‘on the road’ by about 08.30 with the first stop being the Mount Solomon lookout near Glen Helen. From there we went to Ormiston Gorge, with about half the group (us included) doing the 2 hour walk with our Tour Guide and the others walking up and back along the bottom of the Gorge. Our Tour Guide cooked hamburgers for lunch on one of the gas barbecues at the camping area.

After lunch we proceeded east along (Albert) Namatjira Drive to Ellery Creek / Big Hole where we spent some time relaxing in the sun near the edge of the water hole. I headed off on my own and climbed part way up the ridge behind the waterhole to explore the cave that can be seen from the edge of the water hole.

It was then on to Wallace Rockhole. On the way in to this ‘dry’ Aboriginal community we were pulled up by the Police who checked to make sure we were not bringing alcohol in to the area. We stopped at the General Store which is run by ‘Ken’ who also happens to be the key tourist person for the community. After leaving our gear in the tents at the Sahara Adventures permanent campsite Ken took us all on a drive/walk up to the Wallace Rockhole while our Tour Guide stayed behind and started preparations for dinner. Ken shared some excellent information with us about the Aboriginal people and concluded the tour by giving us access to the Arts Centre where many of us purchased locally manufactured items. After dinner we all talked for quite some time around the camp fire.

12 May 2006 Wallace Rockhole to Alice Springs

We were on the road by about 06.45. First stop was at the (Albert) Namatjira Monument on Larapinta Drive, then on to Hermannsburg where we dropped off the trailer lightening the load for our first bit of real 4 wheel-driving out to the Finke Gorge National Park where we saw the Kalarranga Lookout and then moved on to Palm Valley to see the ancient palms and rock formations that abound in the Gorge.

After a walk that takes about 1.5 hours we enjoyed a picnic lunch at one of the eating and toilet block areas in the National Park before returning to Hermannsburg to pick up the trailer / check out the local store and head east along Larapinta Drive toward Alice Springs. We spent a couple of hours at Standley Chasm, and proceeded on to Alice Springs were our Tour Guide took us past a couple of tourist spots and dropped each of us at our accommodation locations. Jan and I stayed at the All Seasons Diplomat Motel. After walking around Todd Mall, we enjoyed a drink at the Todd Tavern and some shopping before dining at the Overlanders Steakhouse.

13 May 2006 Alice Springs to Melbourne

After breakfast we did the “Alice Wanderer ‘Hop on – Hop off’ Alice Explorer Town Tour”, catching the bus out the front of our Motel at 08.50. The tour duration was 1 hour 10 minutes and the trip took us past the Todd Mall, Old Telegraph Station, School of the Air, Anzac Hill (the tour includes an allowance of a couple of minutes to walk around and take some photographs), Panorama Guth Art Gallery, Royal Flying Doctor Base, Alice Springs Reptile Centre, Alice Springs Cultural Precinct (including the Museum of Central Australia, Aviation Museum, Araluen Art and Sculpture Centre, Historic Cemetery [with the grave for Albert Namatjira]), Road Transport Hall of Fame, Old Ghan Train, Date Gardens and the Olive Pink Native Species Gardens.

When we finished the tour we packed up our bags at the Motel and took a cab to the Airport for our 11.30 flight back to Melbourne, arriving 14.25.

Tuesday, 2 May 2006

Ochre Arch History Part 3 – Developments & Events

In this article I briefly outline some of the events and developments which significantly impacted those living in the Pinnacle area:

1860’s Pinnacle was the site of a police Barracks in the hunt for bushrangers Gardiner, Omeally and Hall.

1880s Early in the decade there was an influx of settlers from Victoria and they took up all land available for selection on “Bogolong run” in what is known as the Piney Range area. The word ‘Bogolong’ means “bulldog-ant” in Aboriginal language.

1882 EHK Crawford commenced erecting the Pinnacle homestead (75,000 bricks!)

1888-9 4 reasonably local Hotels were in operation:

* Selectors Return Hotel at Piney Range - Elizabeth Butler proprietor

* Nags Head Hotel at Nags Head Bridge - William T Burrett proprietor

* Welcome Hotel at Wheoga - August Brenner proprietor

* Cricketers Hotel at Bogolong - John Bolton proprietor

1889 Part resumption of “Pinnacle run” (Refer OA History Part 2) – to the 4 Good brothers

1908-09 First telephone connection - to the new Grenfell exchange

1912 Pinnacle station, then 21,000 acres, was further ‘cut up and sold’ for Closer Settlement. Messrs Murray and Warren from South Australia bought the 6000 acre (approximately) homestead block at £6-10 per acre. The rest of the property was disposed of in smaller areas.

1916 5,811 acres of Pinnacle were resumed for Soldier Settlement, making it the first (along with Baerami and Manus estates) property ever resumed for this purpose. In October 1917 it was reported that 9 soldiers were successful in the ballot, with the larger homestead block of 1,267 acres going to Victor Crommelin.

1918 The Forbes-Stockinbingall rail line was officially opened in, giving settlers a closer outlet to rail at Garema and Wirrinya for their produce. The settlement had got underway properly - the first, and biggest of its kind in NSW. There were 6 gangs of fencers, four clearing gangs, and six tank sinkers working in the area in August 1918 and some new houses had been erected and bridges installed.

1919 By February the settlers had arranged for contractor Downey to build Pinnacle Hall - opened in March.

Link to Ochre Arch History Part 1

Link to Ochre Arch History Part 2

Link to Ochre Arch History Part 4

Link to Ochre Arch History Part 5

I invite / welcome comments on when the following took place:

* Connection of mains power – Today the charge per km of installing poles etc is around $35,000 per km.

* Local roads being made accessible in all weather

* Upgrade of telephones away from party lines

1860’s Pinnacle was the site of a police Barracks in the hunt for bushrangers Gardiner, Omeally and Hall.

1880s Early in the decade there was an influx of settlers from Victoria and they took up all land available for selection on “Bogolong run” in what is known as the Piney Range area. The word ‘Bogolong’ means “bulldog-ant” in Aboriginal language.

1882 EHK Crawford commenced erecting the Pinnacle homestead (75,000 bricks!)

1888-9 4 reasonably local Hotels were in operation:

* Selectors Return Hotel at Piney Range - Elizabeth Butler proprietor

* Nags Head Hotel at Nags Head Bridge - William T Burrett proprietor

* Welcome Hotel at Wheoga - August Brenner proprietor

* Cricketers Hotel at Bogolong - John Bolton proprietor

1889 Part resumption of “Pinnacle run” (Refer OA History Part 2) – to the 4 Good brothers

1908-09 First telephone connection - to the new Grenfell exchange

1912 Pinnacle station, then 21,000 acres, was further ‘cut up and sold’ for Closer Settlement. Messrs Murray and Warren from South Australia bought the 6000 acre (approximately) homestead block at £6-10 per acre. The rest of the property was disposed of in smaller areas.

1916 5,811 acres of Pinnacle were resumed for Soldier Settlement, making it the first (along with Baerami and Manus estates) property ever resumed for this purpose. In October 1917 it was reported that 9 soldiers were successful in the ballot, with the larger homestead block of 1,267 acres going to Victor Crommelin.

1918 The Forbes-Stockinbingall rail line was officially opened in, giving settlers a closer outlet to rail at Garema and Wirrinya for their produce. The settlement had got underway properly - the first, and biggest of its kind in NSW. There were 6 gangs of fencers, four clearing gangs, and six tank sinkers working in the area in August 1918 and some new houses had been erected and bridges installed.

1919 By February the settlers had arranged for contractor Downey to build Pinnacle Hall - opened in March.

Link to Ochre Arch History Part 1

Link to Ochre Arch History Part 2

Link to Ochre Arch History Part 4

Link to Ochre Arch History Part 5

I invite / welcome comments on when the following took place:

* Connection of mains power – Today the charge per km of installing poles etc is around $35,000 per km.

* Local roads being made accessible in all weather

* Upgrade of telephones away from party lines

Author Anthony Trollope - Some trivia

In my last blog I mentioned that during the 1870s Frederick Trollope, son of English novelist Anthony Trollope, owned "Mortray Station" which adjoined "Pinnacle run" to the east.

Jan studied Anthony Trollope's book, 'The Warden', when at University and still has a copy of it. In the Introduction section of The Warden it quotes Trollope's biographer, Michael Sadleir as saying the following about him (in part) "It is true that his flavour is as agreeable to contemporary mentality as it was repellent to the eighteen-eighties; that his candor and his lack of afectation are grateful to an epoch which inevitably is an epoch of reaction from elaborate trifling". I really needed to know that!!

Anyway, Anthony Trollope was an extremely prolific writer of great fame and is also attributed with inventing the famous pillar (red mail) boxes in the United Kingdom. Wikipedia has a detailed write up on Anthony Trollope at http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Anthony_Trollope#Biography

Jan studied Anthony Trollope's book, 'The Warden', when at University and still has a copy of it. In the Introduction section of The Warden it quotes Trollope's biographer, Michael Sadleir as saying the following about him (in part) "It is true that his flavour is as agreeable to contemporary mentality as it was repellent to the eighteen-eighties; that his candor and his lack of afectation are grateful to an epoch which inevitably is an epoch of reaction from elaborate trifling". I really needed to know that!!

Anyway, Anthony Trollope was an extremely prolific writer of great fame and is also attributed with inventing the famous pillar (red mail) boxes in the United Kingdom. Wikipedia has a detailed write up on Anthony Trollope at http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Anthony_Trollope#Biography

Ochre Arch History Part 2 - Out of 'Pinnacle run'

In this article I share information about the development of the local area through to the creation and beyond of ‘Ochre Arch’ (previously ‘Cleveland’) as a distinct property. There are gaps, but this is what I have at present.

In this article I share information about the development of the local area through to the creation and beyond of ‘Ochre Arch’ (previously ‘Cleveland’) as a distinct property. There are gaps, but this is what I have at present.Ochre Arch is in the Land District of Grenfell and was originally part of “Pinnacle run”, first taken up by partners Graham and Croker in about 1839. The term ‘Pinnacle’ is a reference to The Pinnacle – the highest point in the northern part of the Wheoga range.

Graham had been an overseer at Burrangong Station, Lambing Flat (now Young) for a Mr. White. The Gazette of 1848 lists “Pinnacle run” as consisting of 26,880 acres, with Mr. F Hull then listed as the owner. Rodger Freely had “Pinnacle run” in 1854.

The town of Grenfell was gazetted in 1866, and its early wealth and population came from gold mining.

“Mortray Station” adjoined “Pinnacle run” to the east and belonged to Frederick Trollope (son of the author, Anthony Trollope) in the 1870’s. Later it was owned by J.L. Waugh and Little, and soon after “Pinnacle run” and “Mortray Station” came under the one ownership. The combined properties of approximately 67,000 acres were advertised for sale in 1878. It is possible the purchasers were the New Zealand Land and Finance Company, but whoever it was appointed Ernest Henry Kinleside Crawford as Manager and he immediately started clearing and fencing the country.

In 1898 some of “Pinnacle run” was resumed. The exact area involved is not known although some documents suggest it may have been around 6,000 acres. About that time the 4 Good brothers from Victoria took up the properties Wilga, Rutland, Warburton (by Thomas Mark), and Cleveland (by William George).

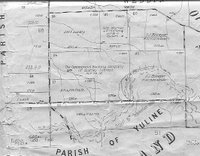

When William George Good took up “Cleveland” it was originally 1,587 acres and some of the documentation suggests that a CL (Conditional Lease?) was registered in 1899. The Parish of Maudry maps show that the property was made up of four Portions which appear in the accompanying image – going from west to east they number 59 (400 acres), then 82 (234 acres), and then 60 (403 acres), and from there south to 42 (550 acres).

In 1909 it was reported that William had planted 200 acres of wheat and was clearing more land.

The Grenfell Historical Society papers state that William George Good “… sold out to the Stein brothers sometime before 1914 and it appears that Mr. George Stein took it over about 1920. George Stein sold out here in 1926 and it passed through various hands …” One of the undated Parish of Maudry maps which was clearly issued after 1922 shows that at that time WG Good still owned Portion 59. The other 3 Portions had transferred to Richard John Kelland & John Murray in 1922 – Portion 82 under a Conditional Purchase, and Portions 60 and 42 under an Additional Conditional Purchase. Another later Parish of Maudry map (which the image above was taken from) suggests that at one point W G Good owned Portion 59, R J Kelland and J Murray owned Portion 82 and F J (Fred) Bokeyar owned Portions 60 and 42. One of the title deed copies suggests that FJ Bokeyar purchased Portions 60 and 42 in 1934 from Messrs Kelland and Murray, and the transaction was in fact a ‘sale-leaseback’.

From 1934 on “Cleveland” has constituted only Portions 60 and 42 in the Parish of Maudry. It’s interesting that two owners over time saw fit to retain the most western and arable Portion of the property they owned at the time of initial sale.

Link to Ochre Arch History Part 1

Link to Ochre Arch History Part 3

Link to Ochre Arch History Part 4

Link to Ochre Arch History Part 5

Ochre Arch History Part 1 – Introduction

I’ve decided to write and publish a series of blog articles that outline the history of the property that Jan and I own. The main sources of information include copies of papers prepared by members of the Grenfell Historical Society in 1967 (kindly provided to me by local resident, Ed Livingstone last month), copies of other documentation that my father, Bruce, had assembled over the years (including copies of old Parish of Maudry maps, title deeds and aerial photographs), discussions with some of the local residents such as Ian Pitt and Harvey Matthews, and accessing some web sites.

The frustrating part of researching anything is that the more one learns the more one wants to know. Consequently I’ve created a separate Word document listing the major questions I still have and in time will hopefully get some of them answered. From the perspective of the blog articles this means I may make later revisions.

In the interest of trying to maintain some level of personal sanity I’ve elected NOT to convert land areas from acres, to hectares. Readers can do this by multiplying the acre figures I quote by 0.404685642. Or as a rough and ready guide, you could simply divide the acres figures by 2.5.

In developing the property history I’ve also learned quite a bit about some of the neighbouring properties. Where I mention these properties it is only done to give context to how our own property and the local community developed.

Link to Ochre Arch History Part 2

Link to Ochre Arch History Part 3

Link to Ochre Arch History Part 4

Link to Ochre Arch History Part 5

Feedback is most welcome, and if you’d like to make a comment it’s a simple as clicking on the ‘comments’ link and following the prompts.

The frustrating part of researching anything is that the more one learns the more one wants to know. Consequently I’ve created a separate Word document listing the major questions I still have and in time will hopefully get some of them answered. From the perspective of the blog articles this means I may make later revisions.

In the interest of trying to maintain some level of personal sanity I’ve elected NOT to convert land areas from acres, to hectares. Readers can do this by multiplying the acre figures I quote by 0.404685642. Or as a rough and ready guide, you could simply divide the acres figures by 2.5.

In developing the property history I’ve also learned quite a bit about some of the neighbouring properties. Where I mention these properties it is only done to give context to how our own property and the local community developed.

Link to Ochre Arch History Part 2

Link to Ochre Arch History Part 3

Link to Ochre Arch History Part 4

Link to Ochre Arch History Part 5

Feedback is most welcome, and if you’d like to make a comment it’s a simple as clicking on the ‘comments’ link and following the prompts.

Monday, 1 May 2006

In response to Griffeaux’s comment on my last blog

“Griffeaux” made the following constructive comment of my Technology and Lamb Marking blog of 30 April 2006 “Phil, I'd be interested in your comments regarding the economic gains as a result of each of your headings under Technology and Lamb Marking. Also, what environmental gains are made as a result - and, you might ultimately respond on the social impacts of each activity - both short and long term.”

In response:

I’m going to make the assumption that there is not an implied objection to the farmers raising animals for use by humans for food and clothing, and consumers using/consuming such products.

From an economic perspective … each of the activities are undertaken on the basis that “prevention is better than cure” and to a certain extent "short term pain for long term gain" (a bit like getting ones tonsils removed!). For example, the marking process acts as a deterrent to stock thieves and simplifies the process of returning stock if they happen to accidently get out on the road or are stolen and recovered. Castration has an economic benefit to the farmer in that the consumer is prepared to purchase mutton from wethers, where many do not like the taste of the meat from mature / aged rams. I could go on. Oh, and by the way, I read recently that wool constitutes 2.3 % of global fibre consumption, reduced from 4 % in 1999.

From an environmental angle ... some could argue that castration prevents the natural formulation of male only flocks ... in turn reducing the hormonal diversity within an overall flock. Reduced fly strike makes life more comfortable for the sheep and the human carers, but does it reduce the food source for natural predators of flies! Of course the bigger issue from an environmental perspective is the decision making process around how the flocks are managed, and lamb marking is only a miniscule component of this.

From a social angle some will argue that lambs should not be ‘marked’ (in the broader definition) as some of the activities are cruel and that the animal suffers stress. Let’s not kid ourselves; the lambs do feel pain – especially from the tail docking. No doubt there have been scientific tests done that describe the intensity and duration of this discomfort. From my own observations most lambs seem to go straight back to feeding within a short period after marking process is concluded, and after 24 to 48 hours seem to be bouncing around the paddock with the same level of vigor as before the procedure. Against this is the chronic suffering that can occur from fly strike – and hear I’ve seen sheep that have had the walls of their stomachs with holes in them made by the activities of the maggots. Not pretty at all. For those that have not seen lambs marked the period of time an animal spends in ‘cradle’ restrained is only minutes. Some of the other social benefits of the marking process include product quality (from being able to trace back to individual consumers) and productivity (through improved animal health and tracking of individual animal performance.

One of the activities I was responsible for when helping my wife's brother with the lamb marking was attaching the ear tags to the ears. As I attached each ear tag I couldn't help but think how many of the human race front up for piercing in all sorts of places. Bazaar really!

To have your say, click on 'comments' below and follow the prompts.

In response:

I’m going to make the assumption that there is not an implied objection to the farmers raising animals for use by humans for food and clothing, and consumers using/consuming such products.

From an economic perspective … each of the activities are undertaken on the basis that “prevention is better than cure” and to a certain extent "short term pain for long term gain" (a bit like getting ones tonsils removed!). For example, the marking process acts as a deterrent to stock thieves and simplifies the process of returning stock if they happen to accidently get out on the road or are stolen and recovered. Castration has an economic benefit to the farmer in that the consumer is prepared to purchase mutton from wethers, where many do not like the taste of the meat from mature / aged rams. I could go on. Oh, and by the way, I read recently that wool constitutes 2.3 % of global fibre consumption, reduced from 4 % in 1999.

From an environmental angle ... some could argue that castration prevents the natural formulation of male only flocks ... in turn reducing the hormonal diversity within an overall flock. Reduced fly strike makes life more comfortable for the sheep and the human carers, but does it reduce the food source for natural predators of flies! Of course the bigger issue from an environmental perspective is the decision making process around how the flocks are managed, and lamb marking is only a miniscule component of this.

From a social angle some will argue that lambs should not be ‘marked’ (in the broader definition) as some of the activities are cruel and that the animal suffers stress. Let’s not kid ourselves; the lambs do feel pain – especially from the tail docking. No doubt there have been scientific tests done that describe the intensity and duration of this discomfort. From my own observations most lambs seem to go straight back to feeding within a short period after marking process is concluded, and after 24 to 48 hours seem to be bouncing around the paddock with the same level of vigor as before the procedure. Against this is the chronic suffering that can occur from fly strike – and hear I’ve seen sheep that have had the walls of their stomachs with holes in them made by the activities of the maggots. Not pretty at all. For those that have not seen lambs marked the period of time an animal spends in ‘cradle’ restrained is only minutes. Some of the other social benefits of the marking process include product quality (from being able to trace back to individual consumers) and productivity (through improved animal health and tracking of individual animal performance.

One of the activities I was responsible for when helping my wife's brother with the lamb marking was attaching the ear tags to the ears. As I attached each ear tag I couldn't help but think how many of the human race front up for piercing in all sorts of places. Bazaar really!

To have your say, click on 'comments' below and follow the prompts.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)